Pulling Back The Curtain on the Softbank Vision Fund

If you're interested in the inner workings of the venture capital industry, paying attention to the proposed WeWork IPO is a great place to start. Last week I wrote about the IPO in terms of some of the problems on the company side.

But Softbank Capital, WeWork's largest investor by far, deserves scrutiny here as well. And by digging in a bit on how Softbank contributed to the WeWork IPO mess, we can understand a bit better some of the dynamics at play in venture capital.

Let's start by unpacking some basics about how venture capital funds work.

The job of a venture capital firm is to raise money from investors, and then provide those investors a return on their investment that beats other investment vehicles, such as bonds or the stock market. The job of a venture capitalist isn't to help entrepreneurs build great companies, although that is a reason why many investors enter venture capital. Their primary job is to invest other people's money and provide great returns.

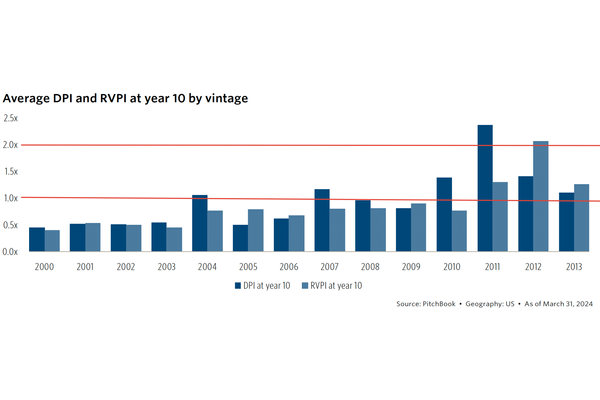

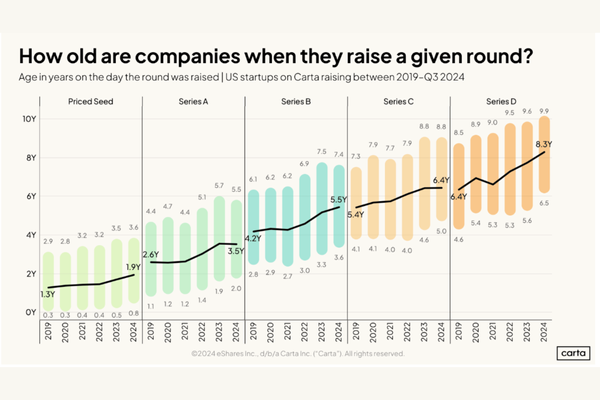

A typical venture fund has a life of 10 years or more. Startup exits over the years have taken longer and longer to achieve. Companies don't rush to IPO anymore. And M&A activity comes in fits and spurts. So it can take years for even great companies to exit and return their gains back to a venture fund portfolio.

However, and this is important, venture funds typically fully invest the money in a fund within the first 2 years of raising the fund. So what do they do once they've invested a fund, and are waiting for returns to start rolling in?

They raise another fund so that they can continue to invest in new startups.

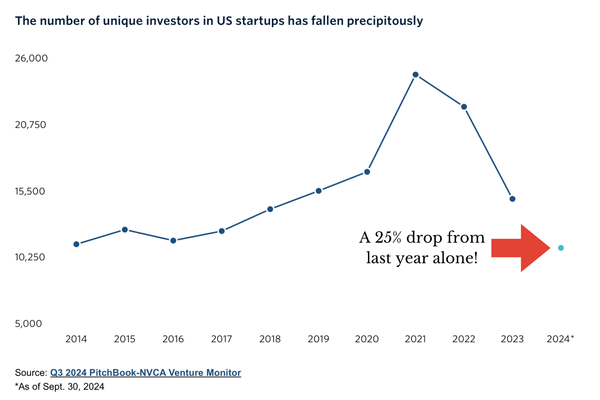

Which creates an interesting dilemma. If a VC firm is going to have to go back out to raise their next $50 million venture fund, how can they convince investors that they are great at picking companies if their first fund hasn't seen any big exits yet to provide returns back to investors?

The answer is that venture firms can mark up the value of their portfolio as long as there is a subsequent event in a portfolio company that can justify the higher valuation. And one of those subsequent events is a new round of funding by a portfolio company.

Quite simply, if my fund invests in the seed round of a company at a $5 million post-money valuation, and the company then goes on to raise their Series A at a $20 million valuation, I have a 4x return in the value of that company. I haven't realized the value of that return, because the company didn't exit or return any money to my fund.

But in my reporting to my investors, and in my disclosures to future investors when I start to raise my next fund, this unrealized gain contributes to the IRR (Internal Rate of Return) of my fund. I can tell potential new investors that my last fund is up 4X, even though none of my portfolio companies have had an exit and returned cash to the last round of investors.

Ok, so let's take this back to Softbank Capital and WeWork.

Softbank made a huge splash in the industry when it announced its first Vision Fund in 2017. It was a $100 billion fund. It was designed to make big bets in high-growth companies, and it was big enough to crowd out other investors by bidding up valuations more aggressively. We won't touch on the fact that $45 billion of the first fund came from Saudi Arabia's sovereign wealth fund, which caused some consternation from some companies.

Softbank made a huge bet on WeWork, investing over $10 billion in the company over 2 years.

But what's interesting here is that the rise of WeWork's valuation from $20 billion in August 2017, when Softbank invested $4.4 billion, to its current $47 billion valuation, was all powered by Softbank investments. Softbank made every subsequent investment after August 2017. On their own. And they marked up the value of the company. On their own.

If Softbank is marking up WeWork's valuation to $47 billion, is that higher valuation real?

As WeWork has tried to drum up support for its IPO, the markets have suggested that it won't accept a valuation of more than $20 - $25 billion. Which many would still argue is massively overvalued, but that's a different discussion.

Note that $20 billion is the same valuation that the company had when Softbank made its first investment into WeWork in 2017.

So, why would Softbank so aggressively markup the value of a portfolio company through its own successive rounds of investments?

Two reasons.

First, the Vision Fund was an audacious idea from the start, and when you come in so brash and bold, you need to have great returns to brag about. Or else the whole concept of such a large fund can start to unravel.

And the Vision Fund is already struggling to produce positive returns. Another big bet in the fund is Uber, and that investment is currently $600 million under water.

Which leads to the second reason. In July, Softbank announced the Vision Fund 2. Softbank wants this to be a $108 billion fund. Note that it's just a bit bigger than the last fund. This one goes to 11.

But to raise that fund, they need to show that the first Vision Fund produce great returns. With Uber underwater, they would have to aggressively mark up the value of WeWork to try to make the overall fund IRR look positive.

Which is why Softbank is now asking WeWork to delay its IPO for a year. Because if WeWork stays private, Softbank can try to keep touting that marked-up valuation as they raise their second fund.

But if WeWork goes public at $20 billion, Softbank will have to mark WeWork back down to $20 billion. And that's going to put their ability to raise their second fund at risk.

WeWork and Softbank are not reflections of the entire VC and startup community. They present a look into this world when greed and hype take over. It's a warning sign. We should pay attention.