External Events Can Move The Goalposts

In the last two issues of the newsletter, we talked about the importance of taking the time to find product-market fit and choosing the right investors. We also need to consider the external factors that can impact a startup’s ability to raise, sell or pivot to profitability and go it alone.

Potential investors and acquirers can be a fickle group. One moment, your sector is red hot, commanding outsized valuations and a constant flow of meeting requests from potential acquirers. The next moment, valuations have collapsed, investors have moved on, and even bankers won’t take your call to help you run a sale process.

Founders need to remember that their ability to raise that next round of funding is not solely dependent on their ability to execute according to the plan they laid out in their last fundraise deck. Even as you hit your key milestones and carefully manage your runway, events outside your control constantly move the goalposts.

Here are three external events you should always watch as you plan for the future.

The Underwhelming Exit

The potential for a high-value exit in the future, whether through an acquisition or IPO, fuels your startup’s growing valuation. Those hopes can be dashed by the failed exit of a later-stage startup in the same space.

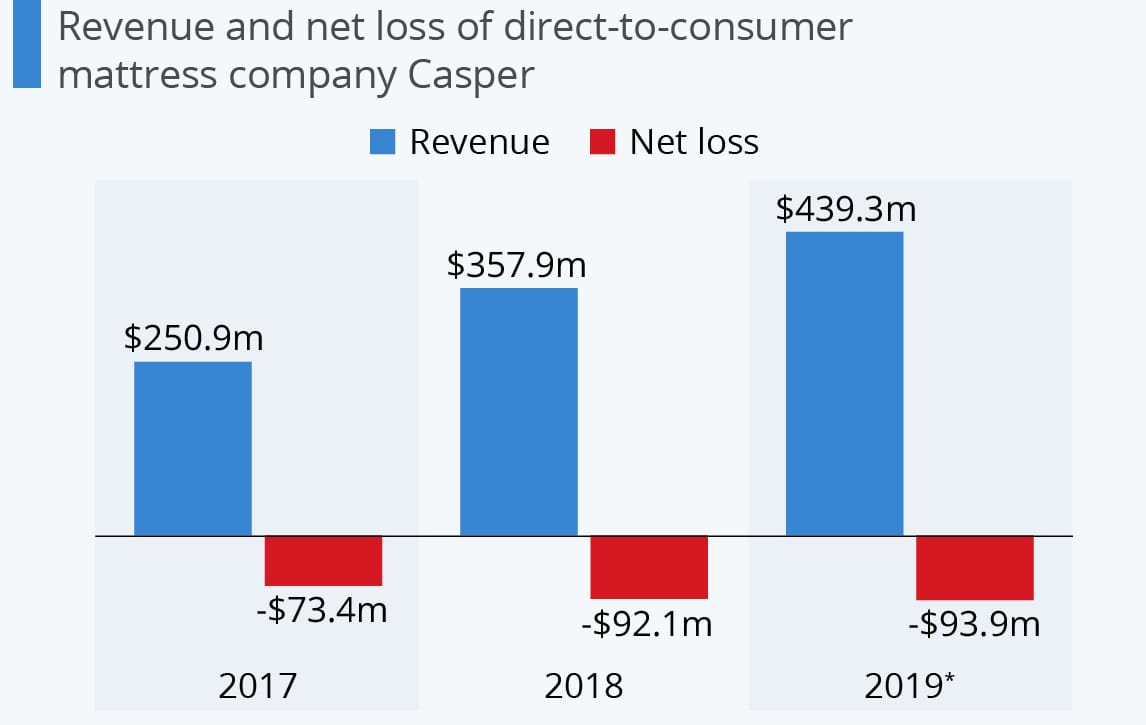

Consider the February 2020 IPO of Casper. The company’s IPO price was $12 per share, representing a market capitalization of $476 million. That was down 57% from Casper’s Series D valuation of $1.1. billion less than a year earlier. By November 2021, Casper was being taken private at under a $300 million valuation. That’s less than the $340 million of venture capital Casper had raised since its founding.

The Casper IPO was a wake-up call for many investors in direct-to-consumer (“DTC”) startups. It quickly became clear that high sales growth fueled by unsustainable marketing spend and cash burn was no longer a sure path to a successful IPO or exit. Suddenly, fundamentals mattered again, and a shorter-term path to profitability became more critical for other DTC startups. Even those outside of the crowded mattress space. Valuations compressed, and many startups with high burn rates and a long path to profitability found that investor interest dried up entirely.

The Rise of Dominant Players

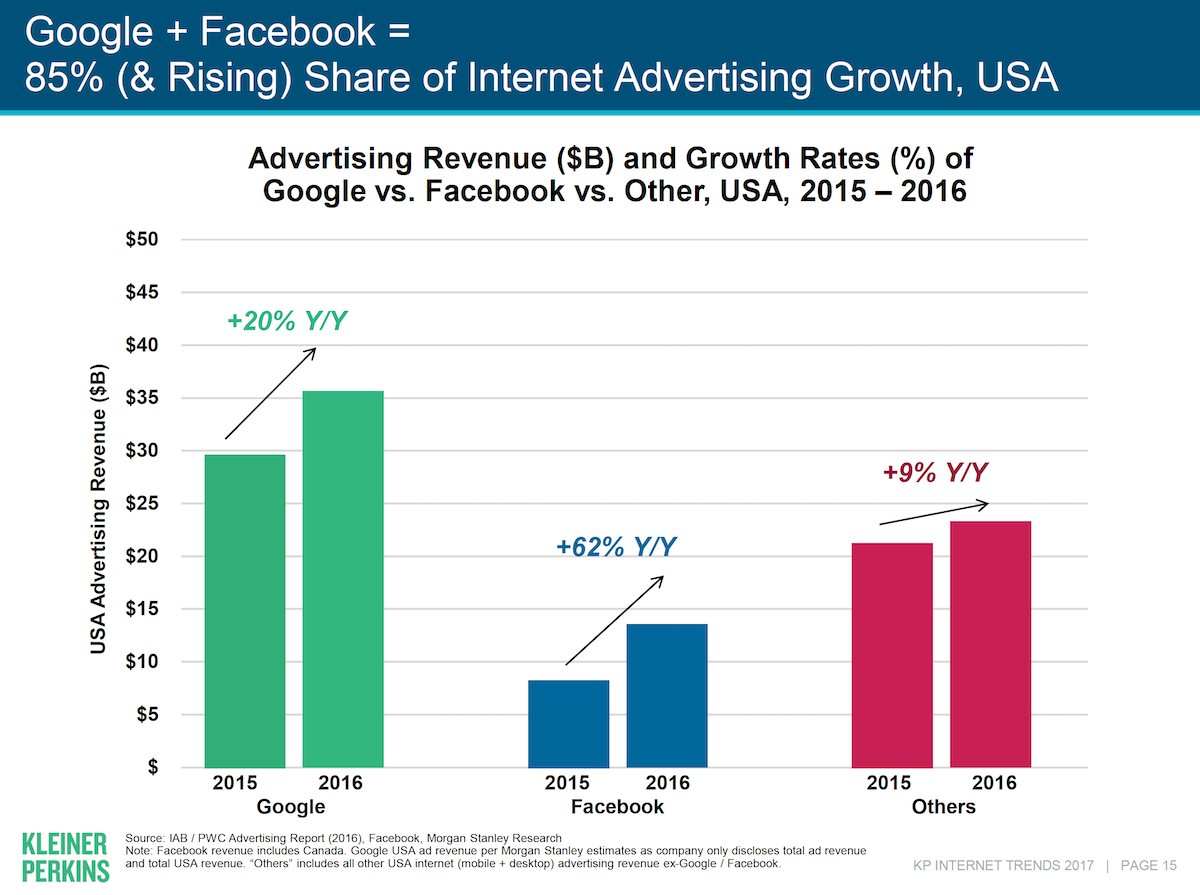

In the first quarter of 2016, 85 cents of every new dollar spent on online advertising went to Google or Facebook. Together, they accounted for over 65% of the total U.S. digital ad market and nearly 70% of the mobile advertising market.

As their growing dominance over the digital ad space became clear, venture-backed digital media startups hit a wall. Investors feared that Google, Facebook, and eventually Amazon would dramatically reduce the growth opportunities for smaller brands, lowering the potential for venture-scale exits in the future. Publishers with tens of millions of monthly visitors were suddenly too small to compete.

I had a front-row seat to this shift as the President of Thrillist Media Group. We were a leading digital publisher with rapidly growing ad revenue, but by 2016 we realized the landscape had shifted. We were suddenly too small to compete effectively for larger ad deals. Our response was to execute a simultaneous four-company merger, rolling Thrillist, NowThis, The Dodo, and Seeker into one holding company, creating Group Nine Media. Overnight, we had the scale we needed to compete across mobile, social, and video. This increased scale, leveraging shared corporate sales, marketing, and operations resources, shortened the path to profitability and attracted a $100 million investment from Discovery Communications. Many digital media brands that missed this shift were either acquired or ceased to exist.

In the early days of the creation of an entirely new industry, there is often a mad scramble among venture-backed startups to gain traction. Eventually, some startups will break out of the pack, reach a new level of scale, and start to expand their market share. Or more mature companies will move in with their deep pockets and quickly establish dominance (i.e., Facebook and Google). If you’re not one of those breakout companies, don’t ignore that you’re falling behind. Investors will certainly be paying attention. You can try to carve out your niche if you can find a profitable, independent path. Or you need to find more scale, likely through M&A, to stay competitive and enable further growth.

Shifts in Economic Conditions

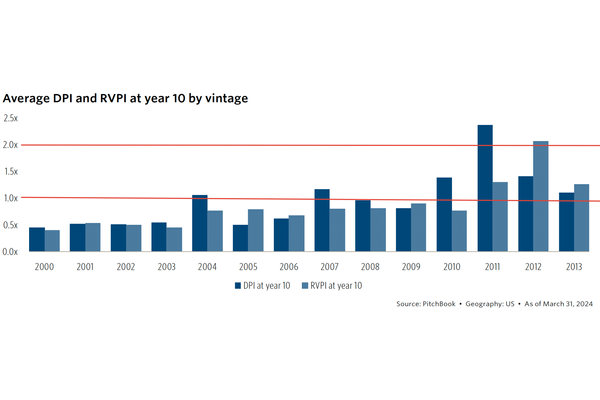

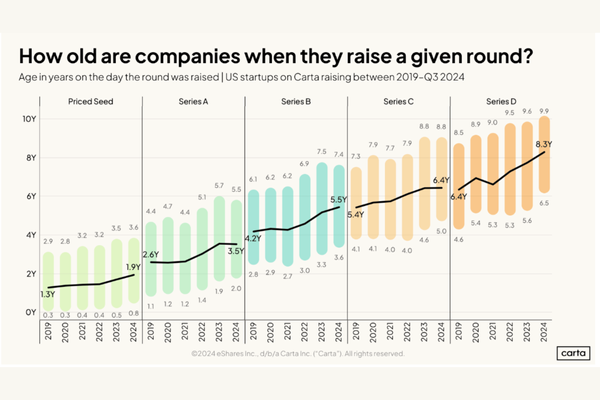

The economy regularly goes through boom and bust cycles. Sometimes changes in the economy come fast and unexpected. The Covid shutdown of March 2020. The Great Recession of 2008. At other times, it’s the more normal cycle of expansion, as we saw over the past decade, and contraction, as we are experiencing right now. These boom and bust cycles highlight two issues relevant to your startup.

First, the boom times bring in the speculators, distorting a market. As we discussed in the last issue of this newsletter, as the number and size of VC funds grew dramatically over the past decade, the increased competition drove up deal size and valuations across every funding stage. Both founders and investors threw discipline out the window.

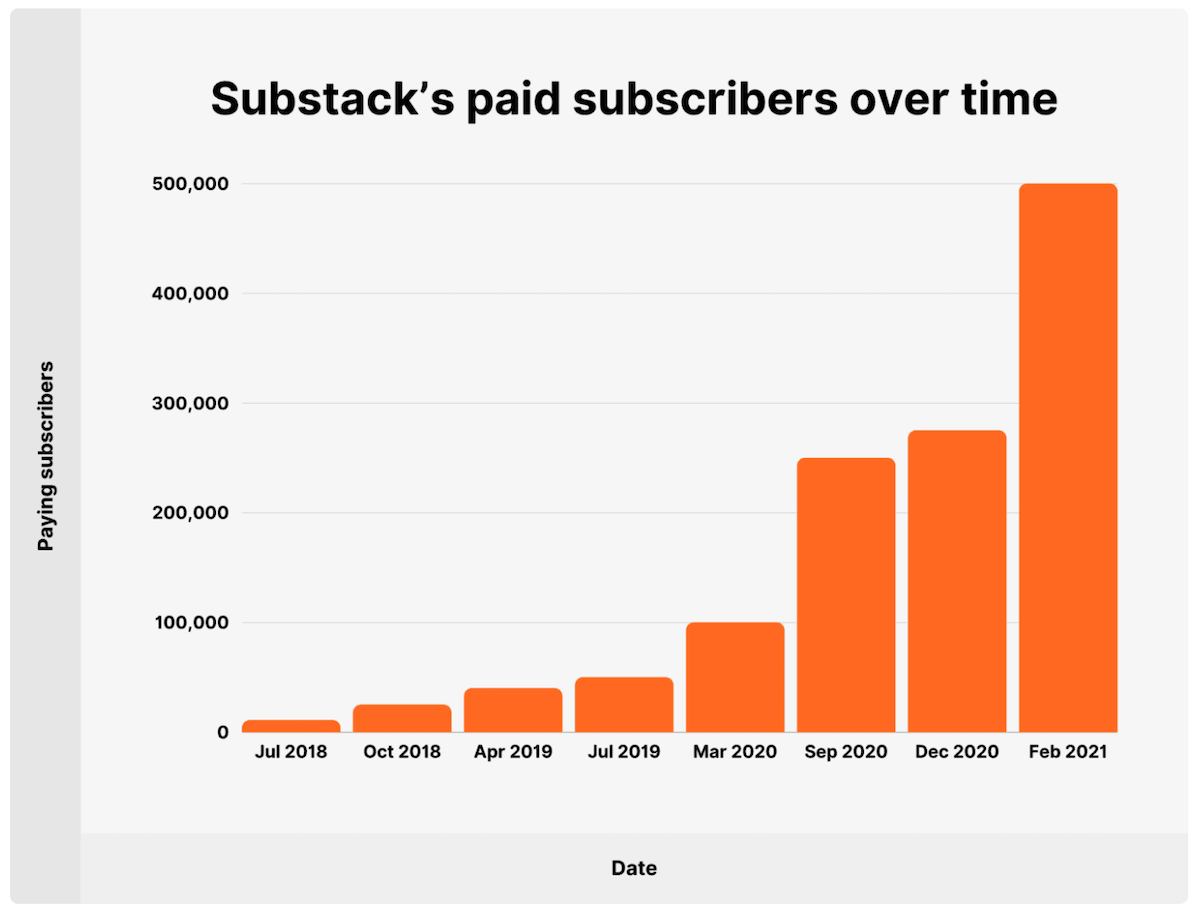

Second, these cycles reinforce how subjective the concept of valuation is. The recent news about Substack’s recent attempt to raise a fresh round of funding is a good example.

Since its founding, Substack has raised over $80 million. Its last round of funding was in March 2021, when the startup raised a $65 million Series B led by Andreessen Horowitz at a reported valuation of $650 million. Perhaps that valuation was driven by the more than 20 million monthly visitors that visited Substack in 2021? Or the growth in paid subscribers over the last few years?

Unfortunately, only 5% – 10% of the total readership are paying subscribers. And Substack only gets a 10% cut of subscriptions. All of this means that Substack’s 2021 revenue was reported to be only $9 million. A valuation of $650 million for a four-year-old startup with less than $10 million in revenue sure does seem like a frothy valuation.

This is a problem even for a well-known startup such as Substack when the market pulls back. Per the NYT:

Substack, the ballyhooed newsletter platform that has lured prominent writers with the promise of cashing in on their relationships with readers, has dropped efforts to raise money after the market for venture investments cooled in recent months, according to people with knowledge of the decision.

Substack held discussions with potential investors in recent months about raising $75 million to $100 million to fund the growth of its business, said the people, who would speak only anonymously because the talks were private. Some of the fundraising discussions valued the company at between $750 million and $1 billion, they said.

That $650 million valuation from Substack’s Series B represented a price-to-sales ratio of over 70x. For some context, Twitter’s price-to-sales ratio is 6x, and Facebook’s is 4x. Substack, like many other startups, is going to have to either find a way to accelerate revenue growth and shorten the path to profitability or adjust their expectations on valuation dramatically. I hope they preserved enough runway to navigate the shift.

Ignore Macro Shifts At Your Peril

I’ve met too many founders focused solely on their own startup’s performance as they march toward their next fundraise, unaware that the ground has shifted beneath their feet. They view underwhelming exits by a competitor as a singular failure of execution rather than consider the risk that there may be fundamental problems with their business model. They dismiss the threat of fast-rising competitors and scoff at much larger companies as slow-moving dinosaurs that can’t match their pace of innovation. They do not respond quickly enough to changes in economic conditions. They don’t notice that investor interest is waning or that valuations are compressing until it is too late.

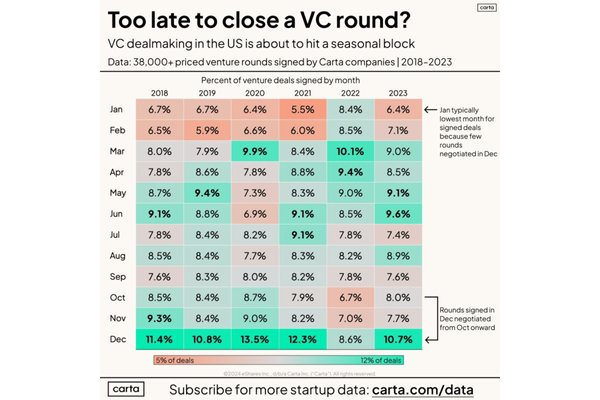

In issue #2 of this newsletter, I suggested having as much as 12 months of runway at the start of your fundraise process. Many would consider this advice too conservative. I’ve seen many founders start their fundraise with only 3-6 months of runway, believing that their overperformance against their strategic and financial plan will bring investors running to invest in their next round.

Pick your head up. Look around. Pay attention to external factors that can block your path and negatively impact your potential outcomes. Don’t march blindly into a planned fundraise process that is no longer viable. Always have enough runway to give you time to adjust to changing conditions. Build a growing platform of product-market fit that enables a pivot to profitability when you need to buy more time or shift strategic direction. External events can move the goalposts. Always be ready to respond to those shifts.