Choose Your Venture Investors Wisely

Choosing your venture investors is one of the most important decisions you'll make as a founder. As you progress through your rounds of venture funding, your investors gain more control over the most important decisions you’ll face: when to raise, when to sell or when to pivot to profitability and jump off the venture track.

You need to understand venture capital's business model and incentives, and how they can impact you and your startup.

Let's start with a quick review of the basics.

A VC's job is not to help founders build great companies. Instead, a venture capitalist's job is to raise money from Limited Partners (‘LPs') to invest in a portfolio of startups that will produce returns that can outperform the stock market.

LPs are primarily institutional investors, such as foundations, pension funds, family offices, university endowments, and sovereign wealth funds. Those LPs view venture capital as an asset class. A part of a diversified portfolio that also invests in bonds, stocks, real estate, and commodities.

That's your startup right there, in a portfolio with 90 other startups, in your VC's 7th fund, as a part of a diversified mix of investments in Stanford University’s endowment fund.

I suspect you describe your startup in far more visionary terms.

Here are four things to remember as you manage the relationships with your investors.

VCs Are Always Thinking About Their Next Fundraise

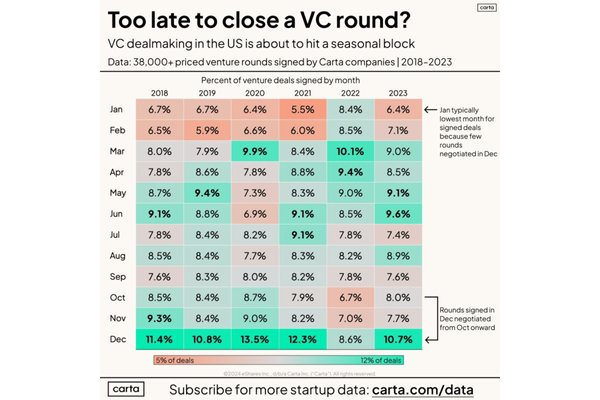

A venture fund has an initial ten-year term. An early-stage VC typically fully invests their fund in a portfolio of startups within its first 18-36 months, holding back a portion for reserves. However, a VC firm always needs to have cash ready to invest in new startups if they want to stay relevant to founders looking for capital. This means that before a firm has fully invested its current fund, they need to raise a fresh pool of capital to support new investments. For that reason, VCs are in a constant cycle of raising a fund, deploying it, and planning for the raising of their next fund.

Venture Capital Has Become More Competitive

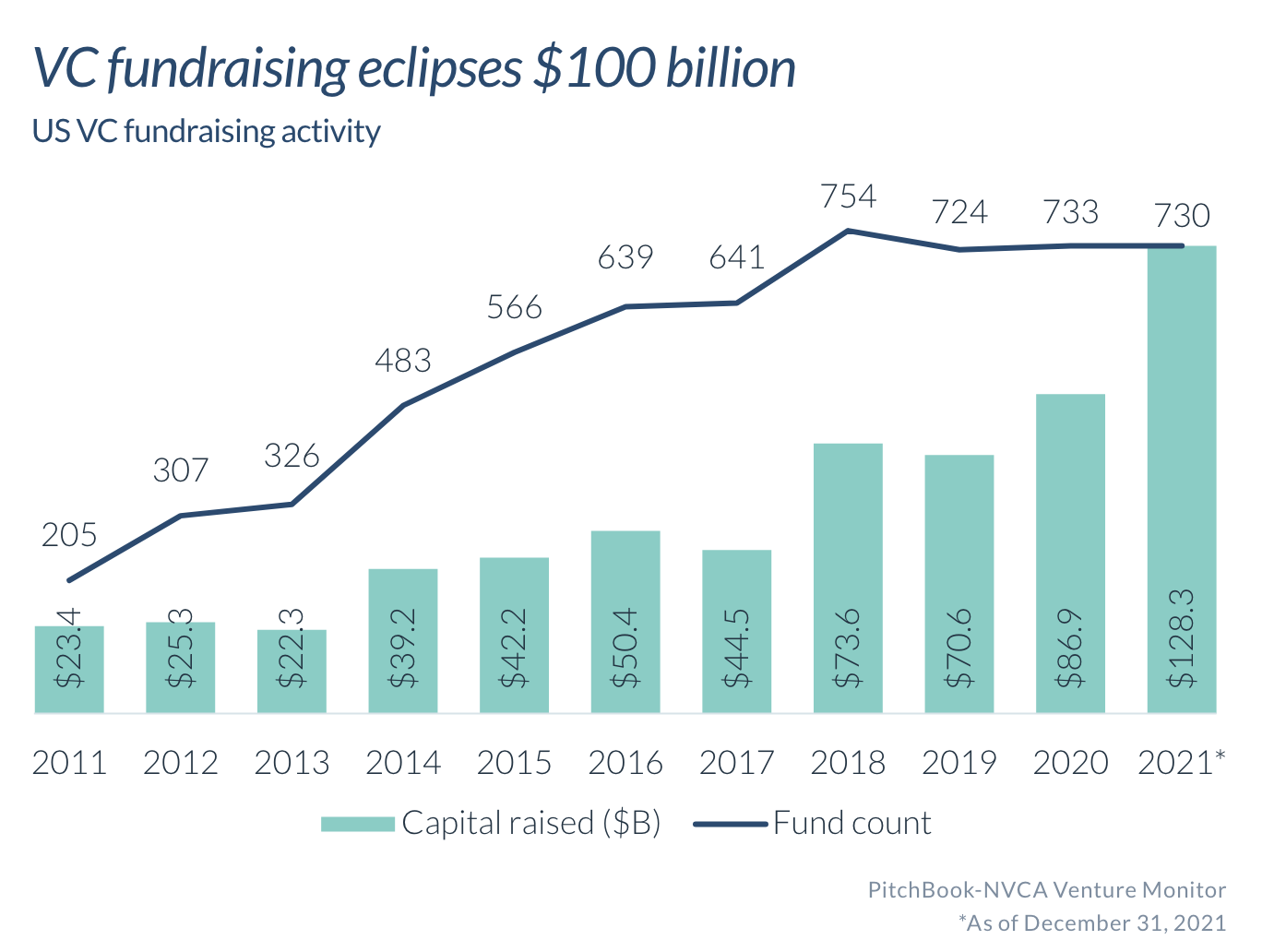

Over the last decade, The U.S. VC industry has become far more crowded and competitive. In 2021, 730 funds raised $128 billion. This compares to only 205 funds in 2011 that raised $23 billion.

That's a lot more funds chasing LPs for investment while also trying to attract the best startups for their portfolio. Through early 2022, this dynamic had made it far easier for founders to raise their next round of funding at higher valuations. But as you might expect, not all investors are created equal.

Chasing Markups Increases the Pressure on Founders

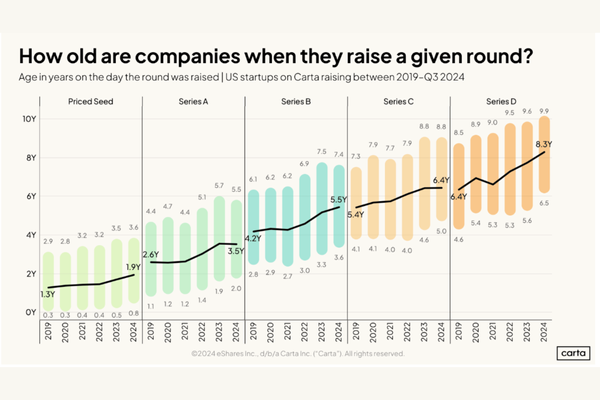

When VCs go out to raise their next fund, LPs use past performance to assess a firm's potential to generate acceptable returns in the future. There's just one problem. Over the last decade, later-stage startups have taken longer to exit, using growing pools of VC cash to fund losses, allowing them to push off an IPO or sale. So how can a VC demonstrate market-beating returns if they don't have enough recent portfolio exits to point to?

The solution to this problem is the 'markup.' If a startup can raise a new round of funding at a higher valuation, earlier investors can markup the value of their investment on their books. Markups increase the reported fair market value of the fund's portfolio, allowing VCs to publish higher projected returns to existing LPs and prospective investors in their next fund. Sure, it's a paper gain. And if the startup ultimately falls back to earth, that gain can vanish. But until that happens, the fund can use markups across its portfolio to boost reported performance.

Unfortunately, in an increasingly competitive VC market, when it takes longer for startups to exit, VCs chase markups to improve perceived fund performance. As you might expect, this dynamic can put pressure on founders to attempt to raise that next round of funding, even if the founder doesn't think their startup is ready.

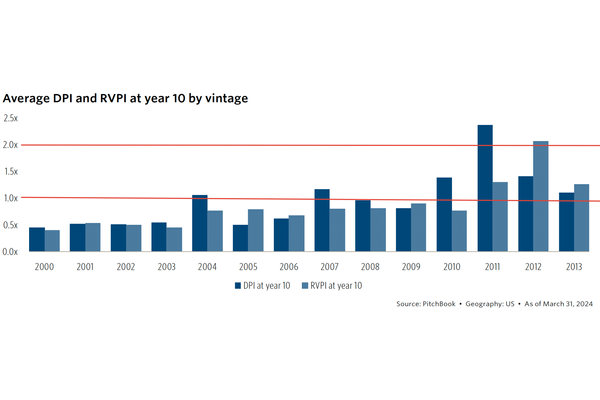

At least Half of VCs Underperform the Stock Market

Since 2000, only the top 25% of venture funds produced returns that meaningfully outperformed the S&P 500. The bottom 50% of venture funds consistently underperformed the market.

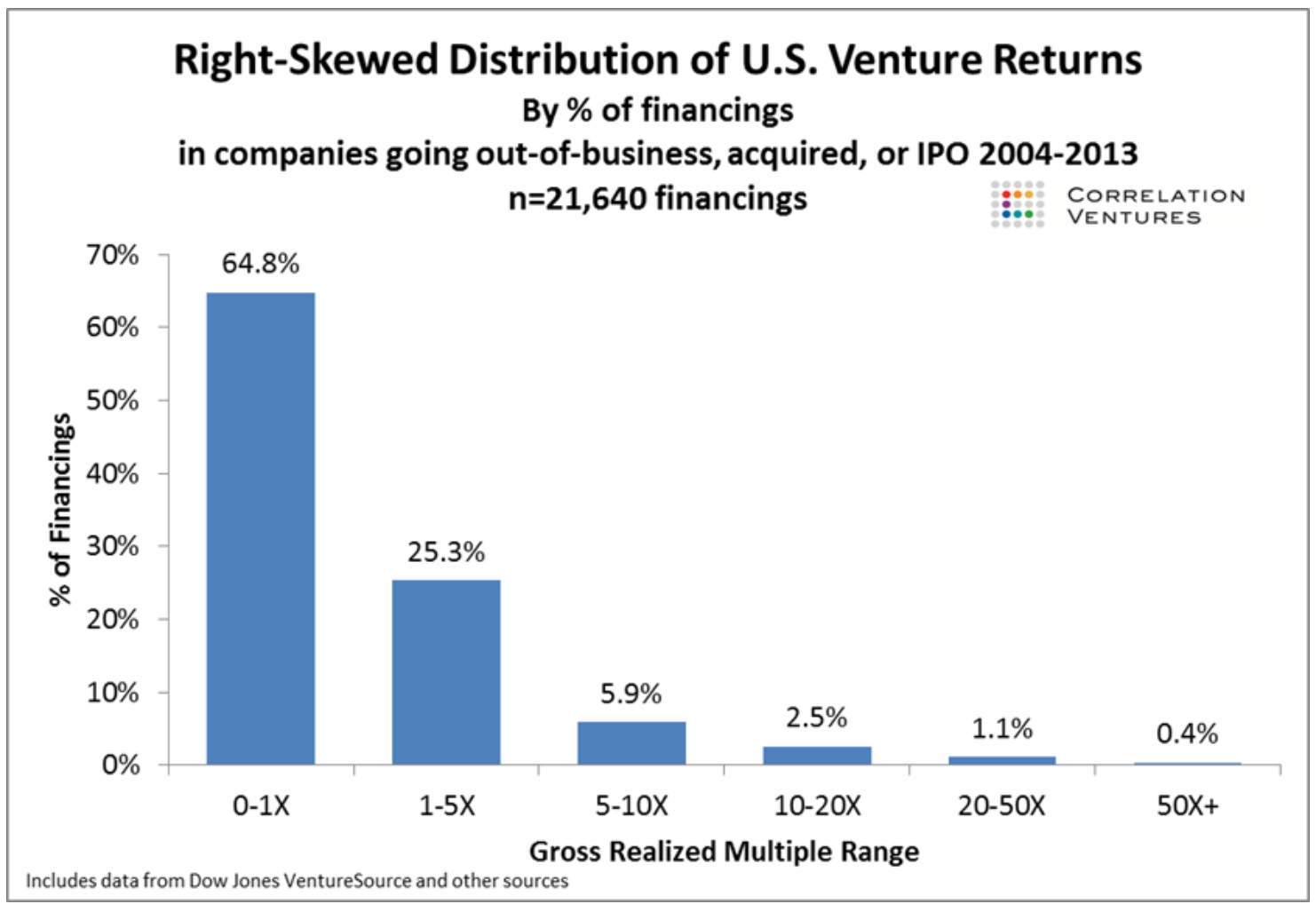

It turns out that producing market-beating venture returns is very difficult. Venture investing is not a game of singles and doubles. In fact, 65% of financings fail to return even 1x of invested capital. From the VC perspective, this high failure rate isn't a problem. It’s a feature of VC, not a bug.

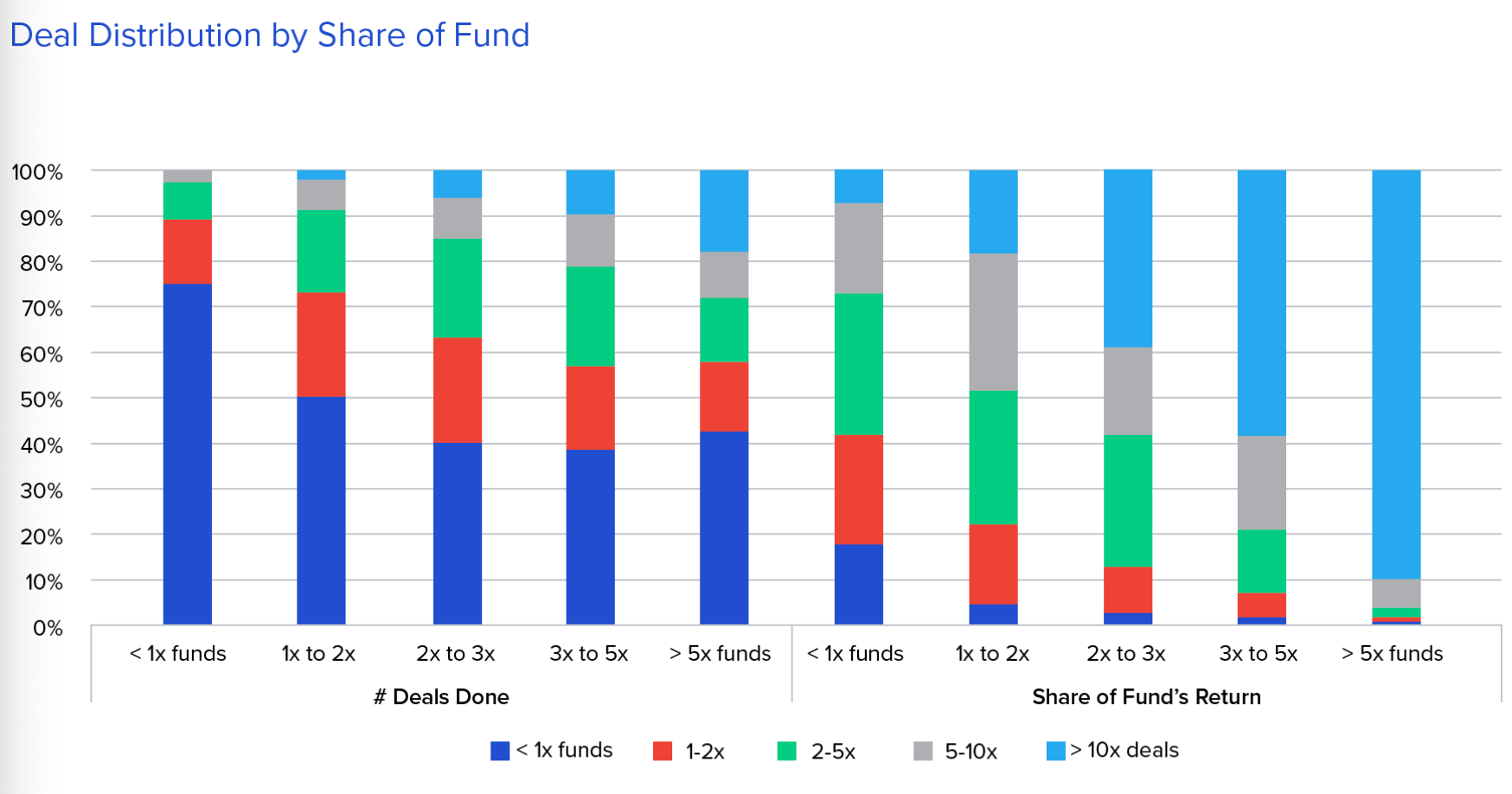

Venture returns follow a power-law distribution, meaning that a few outsized winners in a portfolio generate nearly all of the fund's returns. Strikeouts don't matter as long as the fund hits some home runs. In fact, in the best-performing funds, less than 20% of deals account for 90% of a fund's returns.

For new and underperforming funds, this dynamic presents a unique challenge. 10x home runs are few and far between. And success begets success. The most successful venture firms attract more LPs, allowing them to raise larger funds while attracting the highest potential startups. This cycle of success can make it difficult for lower-performing funds to break through and reach new heights, increasing the pressure on funds to maintain a high level of performance over a long period of time.

Choosing the Wrong Investor Can Limit Your Future Outcomes

When to raise. When to sell. When to shift off the venture track and pivot to profitability. These are some of the most fundamental decisions a venture-backed founder will face. As you raise venture capital and add preferred shareholders to your cap table and board, these are no longer your decisions alone.

Preferred shareholders have important protections that give them the right to block decisions that work against their interests. In board meetings, as you discuss the best path forward, you're focused on your startup and your team, while your investors are first and foremost focused on their portfolio and their LPs.

But as we've seen, not all investors are equal, and not all behave the same way when times get tough and difficult decisions must be made.

The VCs of the best-performing funds can be more supportive when your startup goes sideways. Why? They have built a track record of consistently producing market-beating returns that will keep LPs coming back to future funds. They understand that most startups will fail to deliver even a 1x return on capital, but they have confidence in their ability to build a portfolio that will deliver the returns their LPs expect. They quickly write down underperforming startups, shifting their focus to the highest potential opportunities in each portfolio. This allows for a far more flexible approach to struggling startups, allowing them to be more supportive of a founder when they need it the most.

Conversely, less successful investors must eke out any returns they can from each of the startups in their portfolio. They don't have any home runs to drive the overall portfolio performance. They don't have a strong track record to fall back on. Their ability to raise another fund could be at risk.

One preferred investor with an underperforming fund and standard investor protections can do a lot of damage to a startup if their only goal is to maximize the short-term impact on their portfolio, regardless of the longer-term impact on the founder.

Don't Settle

Given these dynamics, as you raise your next round, you focus solely on valuation and deal size at your peril.

Take the time to develop a target list of investors with a reputation for understanding your space and supporting founders through good times and bad. Do reference checks. Talk to founders in an investor's portfolio, and try to uncover real examples of an investor's behavior at critical inflection points in a startup's journey. Look at prior funds for track records of success.

If you can't attract the investors you want to work with, be wary of settling for investors you don't fully trust. Think about what might be wrong with your business model that could be scaring away the best investors, and think through adjustments you might be able to make. Or slow down, take more time to prove product-market fit, and bring those higher-value investors back into the fold.

Your relationship with your investors can last for years. As with any long-term relationship, don't settle. When you hit a rough patch, and you will, the wrong investor can limit your options and even result in losing control of your startup.

The Current Pullback in Venture Capital

Over the past decade, the explosion in the number of VCs, fund size, deal size, and valuations mirror the broader economic boom that's been largely driven by near-zero interest rates. LPs have been in a constant search for higher yields on their investments. Venture capital has increasingly been seen as a risky yet viable path to better returns. A booming market can make many investors seem successful through the magic of markups and paper gains. But as valuations return to earth, a painful adjustment is coming to VC portfolios and the startups within. We will see a much clearer separation between the best VCs and the rest of the pack. The stress this brings to underperforming VCs will be felt in the boardrooms of startups everywhere. Founders should be prepared.

The Ultimate Form of Leverage and Control

Finally, given the theme of this newsletter, I must point out that a founder's ultimate form of leverage over the direction of their startup is a clear path to profitability and positive cash flow. Even the most difficult investor has very little leverage if you don't need to raise more money. There is an obvious correlation between the length of your startup's runway and the amount of control you can exert at critical inflection points in your startup's journey. The more urgent your funding situation becomes, the less leverage you have.

Choose your investors wisely. Methodically scale product-market fit. Stay in control of your startup.